The Uncanny Valley

May 30, 2019 • 42 views

Have you ever wondered why you felt creeped out when seeing certain life-like robots or when seeing almost realistic video game characters?

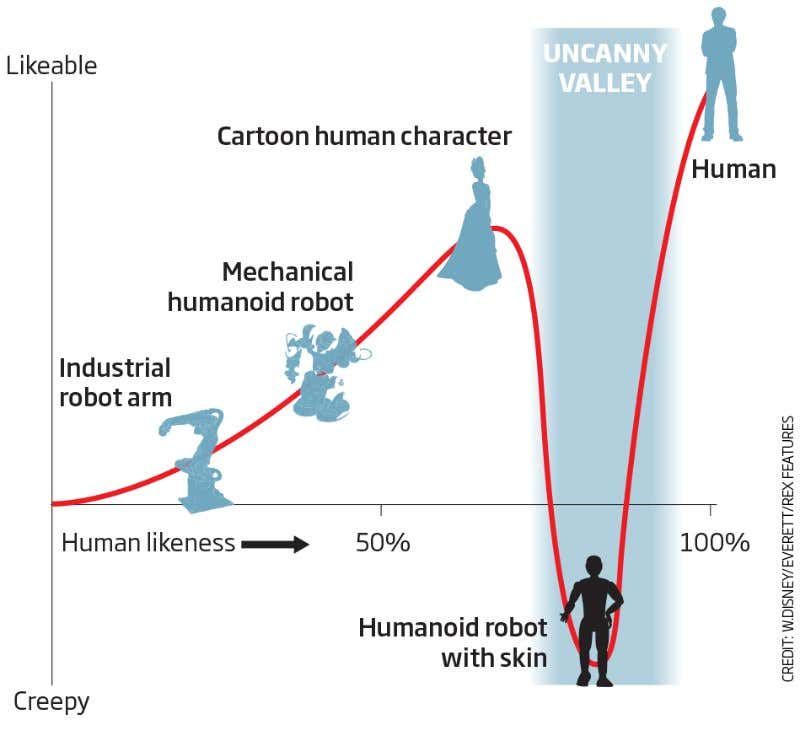

Uncanny Valley, first termed by the Japanese robotics professor Masahiro Mori (and later translated into English by Jaisa Reichardt), is a concept in aesthetics. However, this term is most commonly used when talking about robotics or when discussing animation. The Uncanny Valley refers to a relationship between how close something (like robots or animated characters) is to looking like a human, and our respective emotional reaction to it. Masahiro Mori observed that the emotional reactions to robots were increasingly positive as they became more and more human like, but there was a point where the test object was almost human, but not quite, and the emotional reaction turned suddenly negative. When the robot was fully human like, the reactions were once again positive, to the point where empathy could be established. This data, when plotted on a graph, shows that there is a sudden dip at a point just before achieving complete similarity to humans, and this is called Uncanny Valley.

The reasons for this are many. Humans have evolved to be extremely sensitive to faces and facial expressions. This helps us to interact with others around us, and to understand a lot of non-verbal cues. It is also what is responsible for making us identify human-like faces and expressions in non-human (and even non-living) things, like cars and animals. However, this also means that we easily notice when something is wrong about someone’s face. Thus, the Uncanny Valley is caused by the robot, or animation, crossing the point where we can pretend it is not human, but not achieving the exact likeness. There are a lot of studies on the Uncanny Valley and some suggest that we feel the eeriness as our brains connect the imperfection to possible diseases or pathogens.

This is the reason that many filmmakers today choose to create more stylistic, if cartoonish, characters. To aim for realistic is risky, as it may end up completely backfiring if they do not achieve perfection. Often a single scene is enough to put audiences off, especially children who are usually the target audience for animated films these days. However, this issue does not arise when trying to create realistic renderings of animals, as our brains can still identify expressions enough to empathize, but not consider what it is seeing as human. And so, we can appreciate how realistic Jungle Book (2016) or Lion King (2019) was, but shy away when we see Sofia the robot talk or interact with other humans.