18th Century India- A Dark Age Or Not?

Jun 21, 2019 • 5699 views

The 18th century, that marks a phase in transition between the medieval and modern periods in India, has been subject for historical debate by scholars. The rough timeline, simply put, follows the death of Aurangzeb to the final subjugation of majority of India by the hands of the East India Company of the English. By exploring whether 18th Century India can be certified as a dark age or not, we can also engage further with the layers of historical context as to how different social, political and economic factors played out.. The Mughals were, inarguably a centralised power with a lot of systems in place, whose decline led to a sort of a political disintegration of the country. Viewing the 18th century as a dark age, is to imply that there was a decline- the term ‘decline’ in itself has deep connotations, it assumes that the previous state of order was perfect. It adds an emotional edge, giving all the previous rulers a sense of legitimacy and validation. However, it would be incorrect to assume that the Mughal rule, despite its many successful policies and systems, did not have its own drawbacks, and it is these dichotomies that I intend to break down through the means of this essay.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT-

Aurangzeb’s death catapulted the decline of the empire- for none of the successors could effectively maintain the crumbling empire. This had two effects- on one hand, local powers looked for freedom of their own, and on the other hand, several foreign invasions ensued this disintegration. Nadir shah gave the final blow to the armies of the imperial power in 1739. It was easy for him to do so, for India at the time had a weak administration and a poor military, plundering centres of power such as Delhi. It is popularly imagined that a sort uniform system of rule was followed during the Mughal Empire, which tried to encompass the elements of tax collection/ revenue systems, maintain law and order as well as a strong military that facilitated expansion and prevented invasion. However, some historians look at it through a different lens- wherein they compared the system to “A patchwork quilt, rather than a wall-to-wall carpet of uniform rule.”(Marshall, 4) Resistance to the Mughal authority was evident much before the death of Aurangzeb. Taking the case of Rajput chiefs, who firmly disconnected from the umbrella of the Mughal rule, also shows their willingness to exercise their political freedom.

CONTINUUM RATHER THAN CHANGE-

Rather than imagining a sharp deviation from the ways of the Mughal rule, Marshall suggests that we look at 18th century as a continuum rather than a change. He accurately points out that- “To many scholars, neither economic nor the social and cultural dislocations of the eighteenth century look as sharp as they once did.”( Marshall, 3)The structure created by Akbar survived and shaped the cultural and political elements of the Mughal rule.

SUCCESSOR STATES

The successor states integrated several policies of the Mughals, while implementing some new ones of their own. These rulers constructed an administration closely built on Mughal lines (Habib, Irfan, 367).These successor states, for instance, took extensive care, to not curb the rights of the tribal population. “New rulers sought legitimacy for themselves everywhere in religious terms.” (Marshall, 8) How did they achieve this? They set up a formal system for caste ideals, while smoothly maintaining the religious traditions of the previous regime.

Zamindars, who carried local political authority, were often coerced by the Mughals. However, they rebelled whenever they saw the window of opportunity. These kind of intermediaries asserted a lot of importance in the 18th century- as “They gained a stake in the new political order”( Marshall, 9) This political renewal sent a hopeful signal of greater prosperity to these intermediaries.

The 18th century, that marks a phase in transition between the medieval and modern periods in India, has been subject for historical debate by scholars. The rough timeline, simply put, follows the death of Aurangzeb to the final subjugation of majority of India by the hands of the East India Company of the English. By exploring whether 18th Century India can be certified as a dark age or not, we can also engage further with the layers of historical context as to how different social, political and economic factors played out.. The Mughals were, inarguably a centralised power with a lot of systems in place, whose decline led to a sort of a political disintegration of the country. Viewing the 18th century as a dark age, is to imply that there was a decline- the term ‘decline’ in itself has deep connotations, it assumes that the previous state of order was perfect. It adds an emotional edge, giving all the previous rulers a sense of legitimacy and validation. However, it would be incorrect to assume that the Mughal rule, despite its many successful policies and systems, did not have its own drawbacks, and it is these dichotomies that I intend to break down through the means of this essay.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT-

Aurangzeb’s death catapulted the decline of the empire- for none of the successors could effectively maintain the crumbling empire. This had two effects- on one hand, local powers looked for freedom of their own, and on the other hand, several foreign invasions ensued this disintegration. Nadir shah gave the final blow to the armies of the imperial power in 1739. It was easy for him to do so, for India at the time had a weak administration and a poor military, plundering centres of power such as Delhi. It is popularly imagined that a sort uniform system of rule was followed during the Mughal Empire, which tried to encompass the elements of tax collection/ revenue systems, maintain law and order as well as a strong military that facilitated expansion and prevented invasion. However, some historians look at it through a different lens- wherein they compared the system to “A patchwork quilt, rather than a wall-to-wall carpet of uniform rule.”(Marshall, 4) Resistance to the Mughal authority was evident much before the death of Aurangzeb. Taking the case of Rajput chiefs, who firmly disconnected from the umbrella of the Mughal rule, also shows their willingness to exercise their political freedom as soon as they saw the signs of a falling Mughal rule. This led to the inevitable rise of successor states such as Bengal, Awadh or even Hyderabad.

CONTINUUM RATHER THAN CHANGE-

Rather than imagining a sharp deviation from the ways of the Mughal rule, Marshall suggests that we look at 18th century as a continuum rather than a change. He accurately points out that- “To many scholars, neither economic nor the social and cultural dislocations of the eighteenth century look as sharp as they once did.”( Marshall, 3)The structure created by Akbar survived and shaped the cultural and political elements of the Mughal rule.

SUCCESSOR STATES

The successor states integrated several policies of the Mughals, while implementing some new ones of their own. These rulers constructed an administration closely built on Mughal lines (Habib, Irfan, 367).These successor states, for instance, took extensive care, to not curb the rights of the tribal population. “New rulers sought legitimacy for themselves everywhere in religious terms.” (Marshall, 8) How did they achieve this? They set up a formal system for caste ideals, while smoothly maintaining the religious traditions of the previous regime.

Zamindars, who carried local political authority, were often coerced by the Mughals. However, they rebelled whenever they saw the window of opportunity. These kind of intermediaries asserted a lot of importance in the 18th century- as “They gained a stake in the new political order”( Marshall, 9) This political renewal sent a hopeful signal of greater prosperity to these intermediaries.

There are two reasons that point towards, as Marshall puts it, the ‘vitality’ of the Mughal Empire. One, that the ideological and bureaucratic structures were favourably adopted by the successor states. Second, the incorporation of Mughal mode of governance extending down South to Nawabs of Arcot also furthered this continuity. The Mughals introduced some systems that allowed room for intermediaries as follows-

Mansabdari System- The system, introduced first by Akbar, determined the rank of a government official, they were put under the broad categories of ‘Zat’ and ‘Sawar’.

Jagirdari sytem- One more system introduced by the Mughals. In this they allotted land temporarily to landlords, and thus delegated the authority to collect tax for their respective lands. However, there was a lack of permanency in their authority, where the zamindars simply refused to cooperate with them. It is one strong line of reasoning that explains the decline of the Mughals.

As Marshall aptly puts it- “If the exercise of Mughal authority had never constituted a uniform system in the seventeenth century, the breaking of links between Delhi and the provinces in the eighteenth century need not necessarily be seen as a political revolution on the scale it is often assumed to have been.”

ECONOMY IN THE 18TH CENTURY-

Most of the academic sources available to understand the economic functioning of this century remain to be through European sources, which offers a myopic vision into its workings. There are some extensive sources from the state of Rajasthan, however, that provide a deeper insight. “ 18th century India was predominantly an agricultural society. Urbanism lay inside agriculture than being set apart from it.”( Marshall, 15).Since prices in states like Rajasthan grew faster, it provided a greater incentive for the farmers to cultivate more per unit of land. Port cities like Surat also flourished, with a booming trade and a growing population.

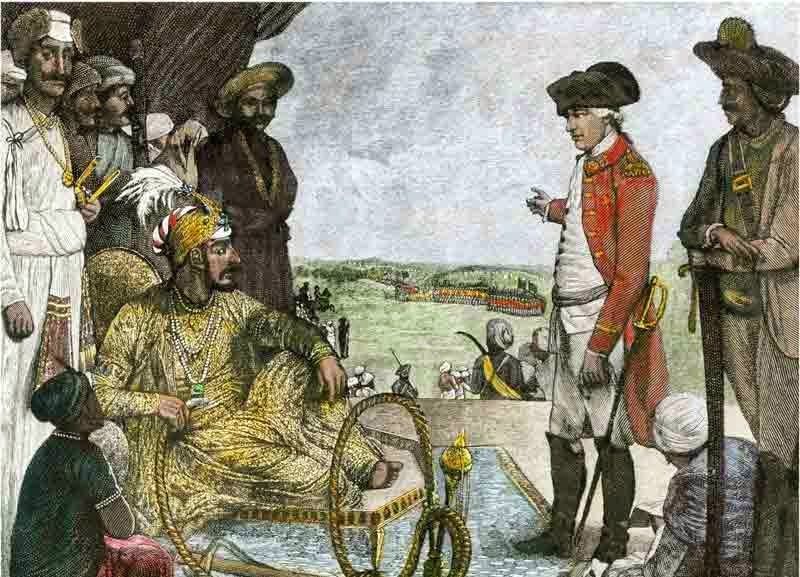

The Battle of Plassey( 1757)-

Important determinant of the political climate, and was indeed reflective of the scattered state of India. This enabled the British to establish a military rule. The betrayal of the Indian forces by the chief, if indicative of how everyone prioritised their vested interests in an imbalancedand extremely divided political order. This war also gave a lasting security of sorts to the British, who could easily focus on their ambitious expansion plans at this point. Delhi, a centre of power even back then, also suffered from the constant plundering and invasions.

The advantage of maintaining the Mughal Empire, as Marshall points out- “A considerable price in terms of disruption was paid for the fall of an imperial system that had spanned most of India. It is, moreover, likely that an effectively functioning Mughal empire would have been able to prevent Iranian and Afghan incursions form the West and might have perhaps even have constrained Europeans to the coast.”(Marshall, 12)

However, it would again be inaccurate to assume that anarchy followed every state that did not have a Mughal hold over it anymore. Marshall takes the example of Awadh and Bengal and describes the change in political order largely as peaceful. Thus, as Marshall neatly sums it up, “ The simple propositions about the way in which a stable Mughal peace gave way to eighteenth century chaos now looks dubious- since important parts of India largely escaped upheavals.”

Thus one must look at both sides of the coin of 18th century India in order to unravel and comprehend the subtleties of economic, political and social context of that time.

There are two reasons that point towards, as Marshall puts it, the ‘vitality’ of the Mughal Empire. One, that the ideological and bureaucratic structures were favourably adopted by the successor states. Second, the incorporation of Mughal mode of governance extending down South to Nawabs of Arcot also furthered this continuity. The Mughals introduced some systems that allowed room for intermediaries as follows-

Mansabdari System- The system, introduced first by Akbar, determined the rank of a government official, they were put under the broad categories of ‘Zat’ and ‘Sawar’.

Jagirdari sytem- One more system introduced by the Mughals. In this they allotted land temporarily to landlords, and thus delegated the authority to collect tax for their respective lands. However, there was a lack of permanency in their authority, where the zamindars simply refused to cooperate with them. It is one strong line of reasoning that explains the decline of the Mughals.

As Marshall aptly puts it- “If the exercise of Mughal authority had never constituted a uniform system in the seventeenth century, the breaking of links between Delhi and the provinces in the eighteenth century need not necessarily be seen as a political revolution on the scale it is often assumed to have been.”

ECONOMY IN THE 18TH CENTURY-

Most of the academic sources available to understand the economic functioning of this century remain to be through European sources, which offers a myopic vision into its workings. There are some extensive sources from the state of Rajasthan, however, that provide a deeper insight. “ 18th century India was predominantly an agricultural society. Urbanism lay inside agriculture than being set apart from it.”( Marshall, 15).Since prices in states like Rajasthan grew faster, it provided a greater incentive for the farmers to cultivate more per unit of land. Port cities like Surat also flourished, with a booming trade and a growing population.

The Battle of Plassey( 1757)-

Important determinant of the political climate, and was indeed reflective of the scattered state of India. This enabled the British to establish a military rule. The betrayal of the Indian forces by the chief, if indicative of how everyone prioritised their vested interests in an imbalancedand extremely divided political order. This war also gave a lasting security of sorts to the British, who could easily focus on their ambitious expansion plans at this point. Delhi, a centre of power even back then, also suffered from the constant plundering and invasions.

The advantage of maintaining the Mughal Empire, as Marshall points out- “A considerable price in terms of disruption was paid for the fall of an imperial system that had spanned most of India. It is, moreover, likely that an effectively functioning Mughal empire would have been able to prevent Iranian and Afghan incursions form the West and might have perhaps even have constrained Europeans to the coast.”(Marshall, 12)

However, it would again be inaccurate to assume that anarchy followed every state that did not have a Mughal hold over it anymore. Marshall takes the example of Awadh and Bengal and describes the change in political order largely as peaceful. Thus, as Marshall neatly sums it up, “ The simple propositions about the way in which a stable Mughal peace gave way to eighteenth century chaos now looks dubious- since important parts of India largely escaped upheavals.”

Thus one must look at both sides of the coin of 18th century India in order to unravel and comprehend the subtleties of economic, political and social context of that time.