Water Crisis In Chennai.

Jun 30, 2019 • 3 views

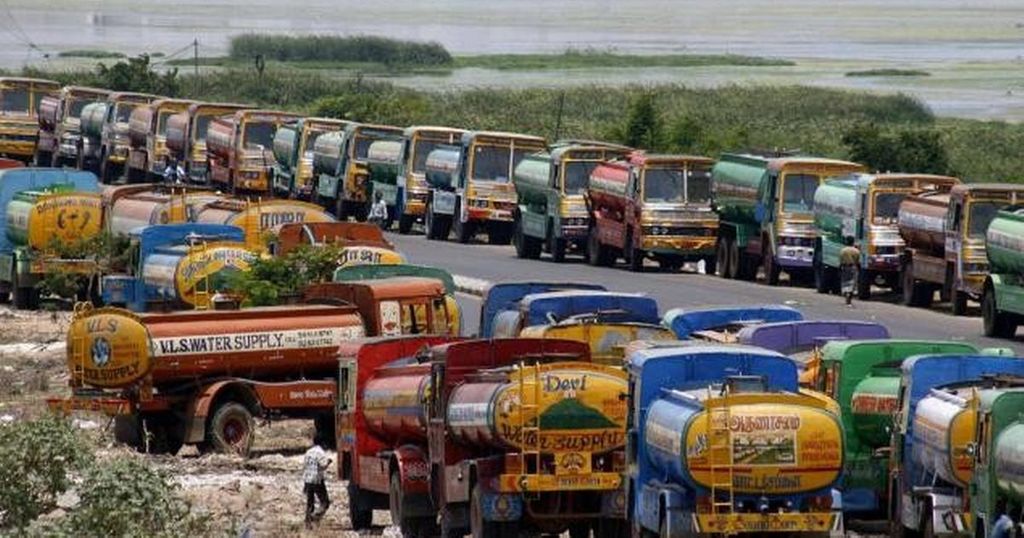

With all the four reservoirs that cater to the 4.64 million population of Chennai city having gone dry, India’s sixth largest city has run out of its drinking water.

Chennai, the sixth-largest city in the country is going through a severe water scarcity.

The four reservoirs that supply water to the city are dry, and with groundwater levels having receded, there are altercations at the water supply points.

While there is international attention on Chennai’s current water shortage, in November-December 2015 the city was in similar lime light due to a devastating flood that cost more than 400 lives and billions in rupees in damages.

This swing between too much and too little water is the story of Chennai’s increasing vulnerability to climate change.

The water shortage in Chennai has made international news, with attention focused on cities running dry. There was news of Cape Town in South Africa running dry and projections about Bengaluru following suit in not-so-distant future.

Globally, with more people moving into cities for their employment and livelihoods, and with many smaller urban centres turning into bigger cities, the fear and concern is genuine. Cities are locations of consumption, where the residents are either unaware or do not care from where they get their natural resources. It is only during crisis situations such as this do the city residents introspect on their consumption loops and ecological footprints.

In addition to international media coverage about Chennai’s situation, celebrity voice was added when Hollywood actor Leonardo DiCaprio talked about the city’s situation through an Instagram post.

Chennai’s problem is that its water availability is mostly from outside the city and not from within the surface of the metropolis. The four reservoirs are located upstream of the city and divert the water of the Kosasthalaiyar, Cooum and Adayar rivers. When these three rivers plus Araniyar flow through the city, they have lost their incoming water and carry the waste that fall into them. Thus, their ability to recharge the aquifer is dramatically reduced in the city.

Over the decades, Chennai lost its ability conserve water in situ, with all the interventions bringing water from outside into the city. Historically, water has been moved into Chennai from Veeranam lake in Cuddalore district, and from the Krishna river in Andhra Pradesh. In more recent years, two 100 million litres per day (mld) desalination plants are operational, and another 150 mld plant is in the development process.

There is a law to harvest rainwater, but then …

In 2001, when Chennai was going through a similar water crisis, the then state government passed a legislation. In a first in India to make rainwater harvesting mandatory across all houses and buildings in the state and, the scheme was promoted aggressively. Though only few structures installed were effective, the groundwater levels in Chennai did replenish after a torrential downpour in 2005.

The union government’s report in 2011 titled Groundwater scenario in major cities of Indiastated that the rooftop rainwater harvesting made mandatory by the Tamil Nadu government has indeed improved the water level but due to lack of periodical maintenance, the effect reduced over the period of time.

More than 15 years later, the situation has completely reversed. The Niti Aayog’s reportpublished last year gave alarming details: 21 major cities including Chennai will run out of groundwater by 2020, affecting approximately 100 million people.

Chennai also needs more recycling

“Until 20 to 25 years ago the idea of classical civil engineering was to concretise urban spaces, control the nature and to harness energy. For example, floods merely meant evacuation. Only in recent times, the necessity for civil engineering to work hand-in-hand with environmental science has become mainstream,” said Jeyannathann Karunanithi who works for the International Water Association (IWA) in Chennai.

Environmentalists suggest that reuse and recycle of wastewater as an immediate solution to tackle the water crisis and, a committed and sustained approach to desilt and restore water bodies. Even as the state government is making efforts to launch two more desalination plants to tackle the water woes, environmentalists warn that it will be another ecological disaster as it may affect the sand dunes, lead to sea erosion, damage marine life, and increase the salinity of water table.

According to a 2018 report by the IWA, there is a need to reuse and recycle wastewater. Around 80 percent of all wastewater – one of the most under-exploited resources – is discharged into the world’s waterways creating health, environmental and climate-related hazards. While using more of the dwindling resources, urbanisation has further exacerbated this challenge with increasing wastewater generation.

Chennai already has wastewater treatment mechanism and 15 percent of the city’s water demand is achieved through recycling as per CMWSSB. This may need to increase. For a city that packs 26,553 people in every square km, conserving water is the best way to deal with drought, and also floods.