Madness And Hamlet

Feb 17, 2020 • 11 views

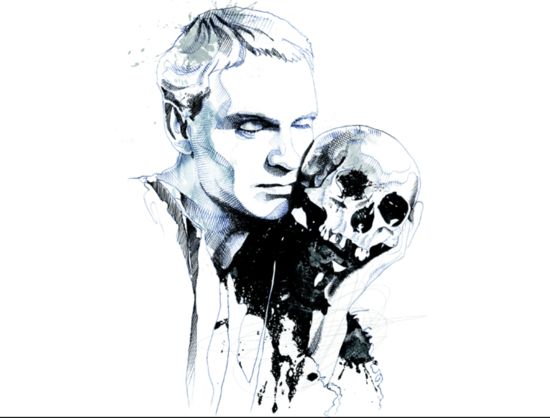

Madness in the Elizabethan theatre played a pivotal role in the development of conflict and gave a sense of theatricality and extravagance to the production. In the versions of Saxo Grammaticus and Belleforest, the hero feigns madness because he is in a point of weakness. Shakespeare uses the story of a hero who is forced to feign madness in order to follow the winding paths that lead to the completion of his self appointed task, but it leads to questioning whether it is a mask for his plan for revenge or a veiled way to criticise society. Incidentally, madness allows the same license as given to a Fool at court and as a character of such prominence Hamlet’s lunacy stimulates the court’s curiosity. Thus, to bring together the two purposes of this pretension, madness can be concluded to be seen as a strategy for the modern hero. Eventually, Hamlet’s mask of madness overcomes him in the sense that the seriousness of his actions can no longer be separated from his selfhood. His ruthless treatment of Gertrude and Ophelia and the act of murdering Polonius brings no remorse and leads to the darkening of his identity. This realisation brings us to question if this young troubled intellectual is pretending a derangement that he is far from experiencing. The Ghost’s revelation brings Hamlet’s state of mind to the brink of his sanity. His numerous moments of lucidity and his constant references to role playing make his behaviour remarkably ambiguous. Yet it is through his soliloquies it is revealed how deep rooted he is in sorrow and grief, and this dramatic device, amply used by Shakespeare in this play, makes his audience the only confidant to Hamlet’s dilemma.

For Hamlet, the encounter with the purgatorial Ghost triggers a kind of mental derangement, and whether it is real or feigned, the extremity of his duress is undeniable. On the other hand, Ophelia’s descent into madness can be looked at as the abandonment of rational thinking. Her descent into grief and madness is marked by a surge of allusions to medieval Catholic forms of piety: St. James, St. Charity and “old lauds”, pilgrimage to the shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham, and other Pre-Reformation religious folklore. Her religious references present the argument: does Ophelia reject Protestant forms of belief because she is deranged or because they offer her less solace than the lauds of medieval Catholicism? The medieval Catholic allusions may be seen as Shakespeare experimenting with the idea of the depiction of a bygone religious era in a Protestant theatre, permissible if spoken by deranged characters. In the first mad scene, Ophelia abruptly pronounces, “They say the owl was a baker’s daughter”, like the old lauds she sings at her death, the folkloric story she recalls here to express her personal anguish is deeply expressive of a lost world of piety. Her network of religious allusions does not conflict with the sexualised nature of her madness. From the early modern Protestant viewpoint, Ophelia’s mingling of eroticism and Catholicism makes the argument that as she slides into the debased madness of eroticism she gives voice to the debased religion of Catholicism with a series of religious utterances. By showing Ophelia’s emotional and imaginative landscape, Shakespeare uses her moments of madness as a blasphemous turn to medieval piety and her final act as the ultimate cost, especially to women, of the English Reformation. The task of accommodating the two irreconcilable religious positions result to madness that both Hamlet and Ophelia resort to while reconciling the past with the present, the former trying to shake free of the spectre of the Ghost and the latter of rationality breaking the mind at the face of loss.