Women & Globalization: The Impact Of Increased Women's Economic Rights On Globalization

May 22, 2019 • 3 views

ABSTRACT

Globalizationis generally studied as a process that extensively impacts nations and peoples across every aspect of society. Empirical and theoretical research largely focuses on this effect, seeking to discover the impact of an increasingly globalized world on the rights and circumstances of historically disadvantaged peoples, particularly women. While research suggests a mixed verdict on the positive and negative results of globalization for women, there is generally a paucity of research on whether an increase in women’s economic rights might enhance globalization, measured by global trade and international investment. This paper employs classical economic theory and quantitative analysis to explore the question of a potential relationship between women’s economic rights and economic globalization. Finding a statistically significant and positive relationship between the two variables, I conclude that increased women’s economic rights, in the form of legal protections, considerably heightens the extent of economic globalization by attracting foreign investors to human capital and deepening the division of labor.

“As it is thepowerof exchanging that gives occasion to the division of labour, so the extent of this division must always be limited by the extent of that power, or, in other words, by the extent of the market” (Smith 2014).

InThe Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith founded a burgeoning field, known now as economics, in an attempt to explain the source of wealth and economic growth among the nations of the world. Describing international markets and trade, Smith is commonly crowned the “father of capitalism” in an age when market economies were developing against the backdrop of colonial, mercantilist empires. Through colonial networks, new peoples were being introduced into global markets, both voluntarily and involuntarily, and contributing goods to the marketplace based on their domestic ratio of land, labor, and capital. Despite the mercantilist structure of the global economy, in which raw materials were exploited from underdeveloped nations for the enrichment of the colonial superpower, Smith began to notice a pattern of specialization that determined production, output, and wealth. Arguing that specialization is intensified by an increase in the size of the market, he predicted that a sharp expansion in the market economy would lead to a considerable sharpening of the division of labor and the specialization that accompanies it. David Ricardo enhanced Smith’s theory with his principle of “comparative advantage,” wherein a nation will specialize in producing goods in which it holds a relative (not absolute) advantage given its factors of production. Comparative advantage determines the patterns ofinternational tradebased on the relative abundance of factors of production within national boundaries.

In the year 1776, Adam Smith revolutionized the field of internationalpolitical economywithThe Wealth of Nationswhile the United States Declaration of Independence proclaimed “all men” to be “created equal,” and thereby all equally entitled to inherenthuman rights. Far from the minds of both Smith and the American founders were the political and economic rights of women, despite the pronouncement of their universally applicable dogma. Less than a century after the Declaration of Independence, prominent reformers, led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, convened in Seneca Falls, New York to declare the universal rights of menand women. The Declaration of Sentiments, molded around Jefferson’s veneratedlanguage, detailed the numerous “injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman” that had the effect of creating an “absolute tyrranny [sic] over her” (Stanton & Mott). Since this sweeping statement of feminist principles in 1848, women have incrementally advanced themselves through greater recognition of legal, economic, and political rights. Regardless of these achievements, the quest for gender equality still marches on in all aspects of both public and private life.

Advertisement

Various explanations have been proposed as to the factors which induced the women’s rightsrevolutionin many countries around the world, including the role of globalization. Yet, according to the theories of Adam Smith and David Ricardo, one might also expect that an increase in women’s economic rights would facilitate a heightening of international trade and globalization. After all, did the large-scale entrance of women into the labor market not represent a massive expansion of the labor pool equipped with new skills and specialities? Neumayer and de Soysa (2011) illustrated the importance of this question best, crediting women’s economic rights with being “instrumentally valuable because it promoteseconomic developmentif women can flourish and freely develop their full potential as talented and productive workers.” (3) Therefore, based on classical theory, I posited the following question: does an expansion in women’s economic rights domestically result in an escalation of countries’ levels of economic globalization? I hypothesize that an increase in women’s economic rights will lead to enhanced levels of economic globalization by increasing international trade and creating a more attractive environment for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

The following paper is split into qualitative analysis of existing scholarly research as well as an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, utilizing variables from the Quality of Government (QOG) dataset. An in-depth examination of the QOG definitions of the variables involved in this paper will follow in succeeding sections, but it should be noted that economic globalization is primarily defined through international trade and FDI. Although many scholars have looked at women’s economic rights as the dependent variable and economic globalization as the central explanatory variable, my research question flips this orthodoxy. Rather, this paper employs women’s economic rights as the central explanatory variable and economic globalization as the dependent variable. The results of the regression between these variables demonstrates a statistically significant relationship between women’s economic rights and economic globalization. Supplementing this finding is a considerable amount of existing research on the positive impact women’s economic rights have had on FDI. Through my analysis, therefore, I conclude that advancements in women’s economic rights have a positive and statistically significant impact on the degree of economic globalization.

Literature Review

At the 2016 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, women’s economic equality was a principal topic of discussion among world leaders. Tian Wei, a former anchor on China’s CCTV and delegate to the Forum, stated that “Any society that fails to harness the energy and creativity of its women is at a huge disadvantage in the modern world.” (Hutt 2016) What is it about the “modern world” that makes women’s access to markets advantageous to economic success? For the purposes of this paper, the modern world, as Wei identified it, will be defined by the words of Bayes and Tohidi (2001), who characterize modernity as including “industry,technology, free markets andcapitalism, science, a largely secularculture, liberaldemocracy, individualism, rationalism, and humanism.” (31) Modern states also tend to be most globalized, as is expected from nations which share an emphasis on free markets and, by extension, free trade. Economic and political liberalism appear to possess a symbiotic relationship that, according to Bayes and Tohidi, provide the perfect conditions for women’s advancement. As globalization is associated with liberalism, these authors identify a causal relationship between globalization and women’s rights which is the opposite of mine: globalization leading to increased women’s economic rights. This school of thought is most prolific within existing research, but it constitutes only one of the three primary schools which exist surrounding the relationship between globalization and women’s economic rights.

In addition to the research arguing a significant correlation between economic globalization and women’s economic rights, scholars have predominantly drawn two other conclusions. Although there are relatively few to no papers focusing on the precise inquiry spotlighted in this paper, one of these conclusions is that increased women’s economic rights, more often denoted as human rights, has measurably attracted greater levels of FDI. Utilizing these papers will provide many of my arguments with qualitative support, although they largely do not address the specific question in this paper. Finally, some critics representing a strain of dependency theory have contended that higher levels of economic globalization either lessen women’s economic rights or that the two variables are entirely unrelated. These three schools will be further investigated in the remainder of this section.

Globalization advancing the cause of women’s rights

Oftentimes, sociologists and economists will opine that international trade and investment create closer bonds between nations and familiarize foreign peoples in less developed nations with aspects of the modern world. Women’s rights, as one of the features of ‘modernity’ so eloquently outlined by Bayes and Tohidi, have been one component of modern states that globalization has promoted. Sociologist Anthony Giddens and economist Will Hutton famously advocated for this relationship by claiming that “globalisation refers to transformations happening on the level of everyday life. One of the biggest changes of the past thirty years is the growing equality between women and men, a trend that is also worldwide, even if it still has a long way to go.” (2001) Globalization, according to this view, should not be confined to simply economic globalization; rather, globalization can take a social and political form as well. Economic globalization is simply synchronous with a larger trend of further political and social globalization.

Social and political globalization, and their impact on human rights as a broad category encompassing women’s human rights, is the primary focus of Twiss (2004), who explores the changes in global human rights conceptions and justifications around the world. Through qualitative historical analysis of prevailing definitions of globalization as well as local cultural justifications for accepting common international norms, Twiss finds that basic human rights have been reconciled across the globe since what he identifies as the climactic event in global human rights history: the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UNDR). He stipulates that the UNDR has resulted in a “practical moral wisdom recognizable across cultural differences” which are “unshakeable, because they are in even wider reflective equilibrium with shared facts, beliefs, and commonalities.” (65) A central element of the UNDR is the “equal rights of men and women,” a fact that helps to explain why Twiss included women’s human rights as a key measure of human rights more generally.

International institutions occupy a special position in the literature regarding globalization’s impact on women’s rights, as was initially demonstrated with Twiss’ work. Other scholars have concentrated on the role of international institutions, primarily highlighting the role of political globalization as an impetus for economic globalization and human rights. Drache and Jacobs (2015) attempt to identify an inherent linkage between the “similar intellectual lineage” of international trade and human rights law, “reflecting a liberal commitment to the importance of the rule of law, private property, economic markets, representative democracy,education, and limits on social inequality.” (4) Echoing the assertions made by Bayes and Tohidi, Drache and Jacobs advance the notion that human rights, which include women’s rights, are linked with globalization in some way. Later in their book, however, they reiterate concerns from economists Dani Rodrik and Joseph Stiglitz who portend social upheaval among workers resulting from “global neoliberalism” (118). Ultimately, many diverse ideas are presented by Drache and Jacobs, but their broad argument is for the intersection between global trade institutions, such as the WTO, and international human rights law like the UNDR.

Such a relationship between trade and human rights, specifically women’s rights, is underscored by the time-series analysis from Gelleny and Richards (2007), which indicates agenerallypositive relationship between economic globalization and women’s economic rights. Broadly examining 130 countries between 1982-2003 through a generalized estimation equation (GEE) regression model, the researchers conclude that “women’s status in a given country appears to be reliably associated with that country’s involvement in the global economy.” (871) This relationship was mixed in several regards; international trade acted as a reliable and forceful stimulant to advancements in women’s economic rights while FDI had no noticeable effect.

Permeating the literature on globalization’s effect on women’s rights is the analysis of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and its impact on domestic women’s economic rights. Keeping with the previously identified pattern of international organizations acting as catalysts for the creation of international norms, the IMF has indeed conducted much research on the topic of FDI and women’s rights. Within one of their most recent working papers, Ouedraogo and Marlet (2018) use data from 94 developing countries between 1990 and 2015 to analyze the impact of FDI on gender inequality. Through their statistical model, the authors discover that “FDI inflows are positively associated with gender development (women are better off) and negatively correlated with gender inequality (hence decreasing gender disparities).” (7) Such an effect is reached through several facets of FDI: by expanding firms and increasing government revenue that can be used for providing equitable public resources; by increasing female specialization and employment through FDI in predominantly female industries; by foreign technologies that bring wage premiums; and by Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Initiatives advocating for gender neutral policies. The fascinating findings from Ouedraogo and Marlet, however, have one stipulation that will actually bolster the relationship identified in this paper. They postulate that FDI may not have these sorts of impacts if policy makers don’t first “ease women’s access to resources in order to fully benefit from FDI.” (32) In other words, women must have the legal opportunity to earn economic profits and own all forms of legitimate property in order to benefit from globalization.

The view that FDI, as a measure of economic globalization, significantly impacts women’s economic rights is substantiated by many scholars in what has grown to be a comprehensive body of literature. Neumayer and de Soysa (2011) study the relationship between economic globalization, measured through both FDI and foreign trade, and women’s economicandsocial rights. The authors utilize the same women’s economic rights variable employed in my own statistical framework, derived from Cingranelli and Richards (2009) Human Rights Dataset. With a multivariate regression of 152 countries between 1981-2007, they confirm a phenomenon they label “spatial dependence,” in which greater trade openness spills-over into higher levels of human rights in all nations except lower income nations. Interestingly, however, this pattern is only true of FDI for investment between middle income nations, a finding that detracts from the conclusions of several other researchers. Despite these seemingly mixed results, Neumayer and de Soysa conclude that “general trade openness as well as spillover effects working via trade links appear to be aspects of globalization that have a beneficial impact on women’s rights.” In this conclusion, economic globalization still has a positive correlation with women’s empowerment, but it is ascribed primarily to trade rather than FDI.

Globalization impeding the cause of women’s rights

Advertisement

Entirely contradictory to the theory of globalization’s positive impact on women’s empowerment is a school which dictates globalization’s further degradation of women’s rights through exacerbated social inequality. Tending to represent an anti-capitalist or dependency theorist sentiment, researchers from this viewpoint emphasize the role of social globalization to an extent unmatched by the research discussed thus far. Arguably most prominent is Seo-Young Cho (2013), who criticizes scholars such as Neumayer and de Soysa, arguing that their reasoning is flawed due to their attempt to “limit globalization to economic integration, which tends to be more closely associated with the outcomes of women’s economic activities rather than the fundamental rights of women” (683). Essentially, Cho contends that women’s rights cannot be treated simply as economic measures of their integration into society; political and social equality are inherently unique from women’s economic outcomes. This approach vastly differs from the baseline assertion made by Bayes and Tohidi, who propounded the “gender neutral frame of reference” taking shape in modern, liberal, and capitalist states (43).

Through a cross-country analysis of 150 nations from 1981-2008, Cho concludes that it is “social globalization that improves women’s rights and empowers women. The impact of economic globalization—trade and FDI—on women’s empowerment is muted when controlling for the effects of social globalization.” (695) At a glance, Cho’s statistical model very closely reflects my own: her measurement of globalization is drawn from the KOF index and her women’s rights evaluation derive from Cingranelli and Richards’ CIRI Human Rights index. Yet, the crucial difference rooted in her theoretical framework is the treatment of women’s economic rights as an inferior form of rights. In other words, Cho concludes that the economic integration of women into the marketplace is secondary to the advancement of their “fundamental rights,” represented by political and social rights (683). This assumption considerably impacted the results of her study, and it was grounded in a theoretical school entirely adverse to the classical economic underpinnings of my own research.

Opponents of economic globalization who denounce the economic inequality inherent in global capitalism often differ from Cho’s foundational assumption, arguing instead that women’s economic rights are indeed a crucial component of women’s rights but that global capitalism simply exacerbates their historical inequality. Echoing concerns of economists such as Dani Rodrik, such critics primarily condemn the volatility associated with international capital flows. Erauw (2009) hones in on the decade-old Canada-Colombia Free Trade Agreement (CCFTA) which loosened regulations in both nations on trade and investment in order to, as the signers claimed, promote economic development and human rights advancements. To support his refutation of the liberal argument that FTAs and international investment advance social equality, Erauw cites the patriarchal structure of international investment law. Erauw continues that international investment law is “‘gender blind’ [rather] than gender neutral. Gender blind means that they ignore differentgender roles, responsibilities, and capabilities and that a given policy is based on information derived from men’s activities” (165). Women’s subjugated position in Colombian society is only worsened, he claims, because international investment ignores their role “within the household, [in] subsistence sectors, and outside of the market economy” (166). Erauw’s Colombian observations are an effective case study example repudiating the role of international institutions and globalization in advancing social equality. His argument, however, actually augments the hypothesis of this paper that claims increased women’s economic rights domestically will result in increased globalization. In order for Free Trade Agreements to succeed, women must be entitled to legal economic and property rights independent of their husbands or fathers.

Despite the evidence put forward by scholars such as Erauw and Cho, there exists a considerable amount of disagreement among scholars identifying a negative relationship between economic globalization and women’s rights. Classical economists would argue that globalization is inextricably linked to economic development, and that international trade and investment are indeed sources of growth for developing nations. Although not extensively focused on globalization as a variable, Gaddis and Klasen (2014) study the legitimacy of a commonly referenced developmental economic theory known as the “feminization U hypothesis” (640). This theory identifies a U-shaped relationship between women’s economic rights (measured solely by female labor force participation rate) and economic development. Through their statistical model, the authors deduce that no such relationship exists in developing countries, where “historically contingent initial conditions are more important drivers of female labor force participation than secular development trends” (676).

Presumably in consideration of economic development theory, Isis Gaddis had already written on globalization’s role in this process with her colleagues Arusha Cooray and Konstantin Wacker (2012). Sampling 80 developing nations between 1980-2005, the authors’ cross-sectional linear regressions lead them to conclude that there is a negligible relationship between globalization, measured by trade openness and FDI, and women’s labor force participation rate. The effect is more significant for young women; they hypothesize this may be due to the “potential rise in the skill premium due to globalization that creates a particularly strong incentive for younger women to invest in education” (20). Such a finding could vindicate some on the opposite side of the theoretical debate, such as Rees and Riezman (2012) who surmised that an emerging industry that creates jobs for females, as would be the result of increased female postsecondary education, would enter the economy into a “virtuous cycle of positive, reinforcing dynamics and reaches a steady state with high per capita income, low fertility, and high female economic activity.” (Gaddis & Klasen 644) Either way, Gaddis and her colleagues ultimately found a net negative relationship between globalization-induced economic development and women’s labor force participation rates.

Women’s rights accelerates economic globalization

Economic globalization, of course, is typically measured through aggregate international trade as well as levels of foreign capital flowing into a nation, commonly calculated by FDI. Literature regarding the impact of increased women’s economic rights focuses almost exclusively on FDI alone, as scholars have largely ignored whether international trade is impacted by increased women’s economic rights. Therefore, the following section will review the research that has indicated a significant and positive impact between women’s rights and FDI. The foundational principle of this argument is the notion that societies with women’s labor force participation and economic rights will be more attractive for foreign investors. Hornberger, Battat, and Kusek (2011) identify “market size and potential” as the largest determinant of new FDI; nations with expanding markets and growing populations will attract greater numbers of foreign investors (2). Although they do not discuss the role of women in this phenomenon, economists like Abney and Laya (2018) have long identified that this growth potential is demonstrated by “Empowering women to participate equally in the global economy” which “could add $28 trillion in GDP growth by 2025.” In other words, economies which include women as equal and valuable economic actors make for a more attractive investment opportunity for foreign companies.

When it comes to studies on the effect of women on FDI, the work of Robert and Shannon Blanton (2011) provides an unparalleled evaluation of the domestic economic and political factors that accentuate economic globalization. Using Bureau of Economic Analysis data from 1982-2007, the Blantons utilized a population-averaged regression model to come to their ultimate conclusion that a significant relationship exists between women’s political rights and FDI. When it comes to economic rights, however, the researchers double down on the “virtuous cycle” identified by Gaddis and Klasen; women’s economic empowerment has a significant attraction to FDI in the long-term but a negative relationship in the short-term. This is due to FDI’s emphasis on educational attainment as a means of human capital development. Women, in other words, are pressured to pursue postsecondary degrees or accept wages below that of their male counterparts. Robert and Shannon Blanton reiterated their findings in 2015, adding that “mobile and efficiency-seeking foreign capital seeks investment hosts with an educated female workforce” but also exploiting the cheaper labor in certain industries where women chronically earn less than men (78). Interestingly, these findings corroborate the assertions made by Gaddis, Cooray, and Wacker (2012) that economic empowerment and educational attainment contradict each other in inviting foreign investment. It should be noted, however, that their research employed cross-sectional analyses and ignored the long-term influence of women’s economic rights and economic globalization. As female educational attainment leads to greater human capital and further economic success, would FDI accelerate? This is a question investigated in my analysis to follow.

Excluded from the KOF measurement of women’s economic rights is the right to own property, a freedom which many economists describe as absolutely critical to economic advancement. Jayme Lemke (2016) researched the Married Women’s Property Acts of the nineteenth century in several states across the US. He reviewed the motivations of state legislatures to grant women property rights and other economic rights. Lemke defined these acts as granting women “the right to write a will without her husband’s consent, the right to engage in business activities as if a feme sole (single woman), the right to refuse to pay her husband’s debts, the right to access her husband’s personal estate after his death, the right to keep wages independently earned, and/or the right to maintain separate property without permission of the court.” (295) The motivation of state legislatures was simple: interjurisdictional competition was pressuring state governments to grant women’s economic rights in order to attract population growth and subsequent economic growth. Although this principle is focused on the United States as a case study, my theory extrapolates these findings into international movement of goods, services, and labor.

Economic rights, as Lemke points out, are usually granted through political processes rather than economic or social evolution. The measure of women’s economic rights employed by most of the researchers thus far has focused on their legal rights to earn income and participate in the workforce. As Adam Smith believed, economic growth is contingent on a “system of natural liberty” in which government protects civil rights and liberties, which naturally include economic rights (Spengler 1976: 168). The notion that political rights and civil liberties enhances economic development, which is deepened by global economic integration, is echoed by Dutta and Osei-Yeboah (2010). They conclude their statistical, OLS regression analysis by stating, “If good political rights and civil liberties exist, then the positive relationship between human capital and FDI inflows is enhanced.” (178) Again, conflating women’s rights with human rights recognized and protected by government is essential to the analysis of this paper. Many of the scholars in the literature assess the impact of human rights, women’s rights, and civil rights on FDI, specifically. Assuming advancements in women’s rights to be elevations in both human rights and civil rights, then it is safe to conclude that these intellectuals have all shared a similar belief in the ability of liberal, democratic rights to attract FDI.

Deficiencies in existing literature

Conclusions very unique from that of my own paper have been drawn by a multitude of scholars, many of whom conducted empirical research of their own to augment their points. Keeping in line with the classical underpinnings of my hypothesis, I identified potential gaps and inconsistencies in their research which justify the central inquiry of my paper. When it comes to the dependency theorist perspective, I believe major theoretical flaws littered their basic framework. They are outlined below.

Gelleny and Richards (2007) critique the flawed nature of the dependency perspective most lucidly by pointing out that “many of the most powerful critiques of globalization reference specific groups or regions and are not theoretically oriented at the country-year or macro levels of analysis.” (855) In other words, scholars like Erauw (2009) and Gaddis (2012; 2014) utilize cross-national analyses or overly specific case studies to arrive at their generalized point rather than examining an overall trend over the course of time. Erauw used his Canada-Colombia FTA case study as evidence of detrimental impacts of FDI, yet the investment he identified was in pre-existing government projects that subjugated women and violated fundamental human rights. Noting the exclusion of women from Colombia’s market economy, Erauw contends that women’s conditions are exacerbated by Canadian multinational corporations. This central assumption is flawed in its understanding of neoliberal economic theory in two ways. First, investment in government projects is not considered the most efficient allocation of resources in a classical sense. Therefore, Colombia’s failure to politically develop is being conflated by Erauw with failure of international investment law. Second, granting women’s economic rights to Colombian women, according to my hypothesis, would work to mitigate the negative consequences of Canadian investment that Erauw identifies.

Another similar notion advanced by Erauw and his colleagues, specifically Gaddis and Klasen (2014), is the conclusion that “initial conditions” must be changed before globalization can work to enhance women’s rights (641). In my theoretical framework, the legal protection of women’s rights represents the extent to which those conditions have been changed, and therefore enable economic globalization. Classical economic theory can account for the conclusions drawn by these scholars, and is actually more in line with their assertions than some might like to admit.

The school which dictates that women’s economic rights, as a form of human capital, promotes economic globalization typically treats international trade as an afterthought. Some scholars include openness to trade as a control variable that helps encourage FDI, but no theoretical grounding is provided to explain any kind of relationship between women’s rights and global trade. Finally, the school of thought which emphasizes a positive relationship between economic globalization and women’s rights is substantial and thorough. It is not the purpose of this paper to question or discredit their conclusions, but rather to demonstrate that the relationship can work in the other direction as well. In order to do this, the literature of dependency theorists might actually prove helpful due to the fact that so many of them identify the obstacle to globalization’s positive impacts as a deficiency of foundational human and civil rights.

Explanation and Hypothesis

Adam Smith wrote hisWealth of Nationsin 1776 and it immediately transformed the intellectual world as economics became a concrete field of study. Central to his thesis was the division of labor that naturally develops in market economies, a division which leads to specialization, increased production, and a price mechanism to measure the societal value of the good(s) being produced. Smith claims that the division of labor, and subsequent specialization, is limited by the extent of the market. He postulated that “The extent of their market, therefore, must for a long time be in proportion to the riches and populousness of that country” (2014). Such a claim indicates that population growth is naturally intertwined with economic growth. It was David Ricardo (1821) who first expanded Smith’s theory to an emerging concept of globalization, thought of by Ricardo solely as international trade of specialized goods. Ricardo claimed that by “increasing the general mass of productions, it [comparative advantage] diffuses general benefit, and binds together by one common tie of interest and intercourse, the universal society of nations throughout the civilized world.” Smith theorized that an expansion in population means an expansion in the extent of the market, which would induce economic growth through the division of labor. Ricardo claimed that the division of labor could also determine international specialization and trade. Based on these two theories, and considering women’s entrance into the market to be another manifestation of an increase in its extent, I hypothesize that greater women’s economic rights will result in increased economic globalization due to its influence on trade.

Both Smith and Ricardo, in addition to contemporary neoclassical economists, believe that the division of labor is the source of growth in a nation. Ricardo claimed international economic development was due to enhanced international specialization and trade. Providing a significant bolster to the connection drawn between their theories and women’s entrance into the marketplace is the work of Tsani (2013). Through an in-depth time-series statistical analysis of 160 nations between 1960-2008, Tsani finds a significant relationship between female labor force participation and economic growth in her specified region of the south Mediterranean. Connecting international trade to economic growth, she found that “increased female labour force participation increases labour supply, thus the cost of labour and wages fall. This drives production costs down and makes exports of the South Mediterranean countries more competitive in the international markets. Reduced prices, resulting from lower labour costs increase private consumption. Higher consumption and investments push GDP to grow.” In other words, female labor force participation deepens the extent of the market which pushes consumption and production up, thereby increasing international trade and economic globalization.

Coupling the previous findings and its theoretical support with the existing literature on women’s economic rights’ attractiveness to foreign investors as a form of human capital (Dutta and Osei-Yeboah 2010; Abney and Laya 2018), this paper’s hypothesis is predicated on the intuition that that both facets of economic globalization, international trade and investment, will be sharpened by women’s economic rights. In the literature review, however, it became clear that many other factors are at work in societies in which women are making great advancements. Primarily, three key factors, or alternative hypotheses, were identified by scholars as having a significant effect on economic globalization:democratizationor political rights, property rights, and economic growth.

Alternative Hypothesis: Democracy

Democracy and FDI have traditionally been regarded as symbiotic, as democratic institutions naturally enhance civil rights and liberties, and therefore human capital. In their review of literature on this topic, Dutta and Osei-Yeboah found that the literature “unanimously agrees that investment and growth will be encouraged if there are constraints on the power of autocratic regimes” (2010). This might be because investors are trying to avoid the sort of government-induced negative circumstances plaguing the Canadian-Colombian FTA that Erauw identified. Further, Lemke (2016) argued that “Whether or not legislators will be motivated to discover and act upon the preferences of individuals depends upon the particular incentive structure of the political system they are operating within.” (292) These authors are trying to point out that, in order for political, economic, or property rights to be recognized and protected, governments must be responsive to popular demand. Democratization can likely account for much of the progress in economic globalization, but I believe this is due to the protections of human rights by democratic governments. Democratization will provide for a useful control variable since women’s economic rights are measured by the extent of legal protections afforded to women within societies.

Alternative Hypothesis: Property Rights

Property rights protections represent a major pillar of classical economic theory; without insurance against arbitrary seizure of personal property, incentives for innovation and investment would be low. Therefore, economic growth and development are centered around property rights protection, and economic globalization is contingent on property rights guarantees. Could it be, then, that women enjoy greater economic rights in nations that grant wide property ownership rights? Ouedraogo and Marlet (2018) conclude their IMF working paper by identifying the relationship between all of these variables, “If countries want to benefit fully from FDI inflows, improving the business environment for women and access to resources need to be lifted so women can enjoy free access to the labor market and to new income.” (7) Women’s property rights are crucial to economic integration, and since it is not explicitly laid out in the CIRI women’s rights index (outlined below), the extent to which societies protect private property ownership will prove beneficial as another control variable. Additionally, Lemke (2016) connects property ownership with democracy, showing correlation between all of these variables, by stating, “In the absence of interjurisdictional competition in the form of nineteenth century US federalism, it is likely that women’s rights to property ownership would have been delayed significantly; and so too the concurrent benefits of property rights—the ability to invest, incentives to become educated and be entrepreneurial, and the opportunity to lead an independent life.” (309)

Alternative Hypothesis: GDP Growth

Nations with an extensive and promising expanding market are prone to increased levels of foreign investment. Scholars Dutta and Osei-Yeboah (2010) stated this phenomenon best by saying, “GDP proxies for size of the market, which may be important for horizontal or market‐seeking FDI, since size reflects the attractiveness of a particular location.” As most economists would argue, economic growth occurs in lockstep with economic globalization, since international trade and investment induces development. And economists like Abney and Laya (2018) contend that women’s entrance into the market represents an expansion in its extent that unlocks trillions of dollars in GDP growth. Therefore, nations with higher per capita GDP will likely enjoy a greater degree of women’s economic rights. This notion will be incorporated as an control variable in the methodology.

Synthesis of Hypotheses

My classical economic framework can account for these explanations since democratic institutions, by economic dogma, are to protect the basic political and economic rights of citizens in order to ensure maximum economic output. These explanations are not alternative explanations, but rather correlated phenomena that share the traits of Bayes and Tohidi’s definition of modern, liberal states. In other words, nations with less autocracy and more democracy will generally grant higher degrees of property rights and women’s economic rights which leads to economic globalization and GDP growth. Therefore, these three rival explanations will be accounted for in my framework as control variables.

Research Design, Data, and Methods

The test in this experiment is an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression that measures data across a time-series, cross national dataset. The dependent variable, economic globalization, is measured from 1970-2014 in 207 nations, with the country year acting as the unit of analysis. As was stated earlier, women’s economic rights is the central explanatory variable in the statistical analysis, while economic globalization is the dependent variable. Cingranelli and Richards’ (2009) CIRI women’s economic rights index is extracted from Quality of Government (QOG) dataset. It is an ordinal variable measured from 0-3 and the descriptions, reiterated from the CIRI index, are listed below.

0. There were no economic rights for women in law and that systematic discrimination based on sex may have been built into law

1. Women had some economic rights under law, but these rights were not effectively enforced

2. Women had some economic rights under law, and the government effectively enforced these rights in practice while still allowing a low level of discrimination against women in economic matters

3. All or nearly all of women's economic rights were guaranteed by law and the government fully and vigorously enforces these laws in practice

The central explanatory variable is a measure of legal rights afforded to women in each nation per year according to the CIRI women’s economic rights index. Economic globalization is a continuous variable extracted from the KOF globalization index and its values range from 0-100. The measurement is bi-faceted, accounting for trade globalization (trade in goods, services, and trade partner diversification) and financial globalization (FDI, portfolio investment, international debt, international reserves, and international income payments). Data is pulled from the 2017 IMF International Investment Position (IIP) and the World Bank Group’s World Development Index (WDI) and consolidated into the KOF evaluation. Based on the analysis in this paper, where economic globalization was split into international trade and investment (measured by FDI) and women’s economic rights was thought of as the degree of legal protections afforded to women, these two indices will provide the proper quantitative counterpart to the qualitative analysis.

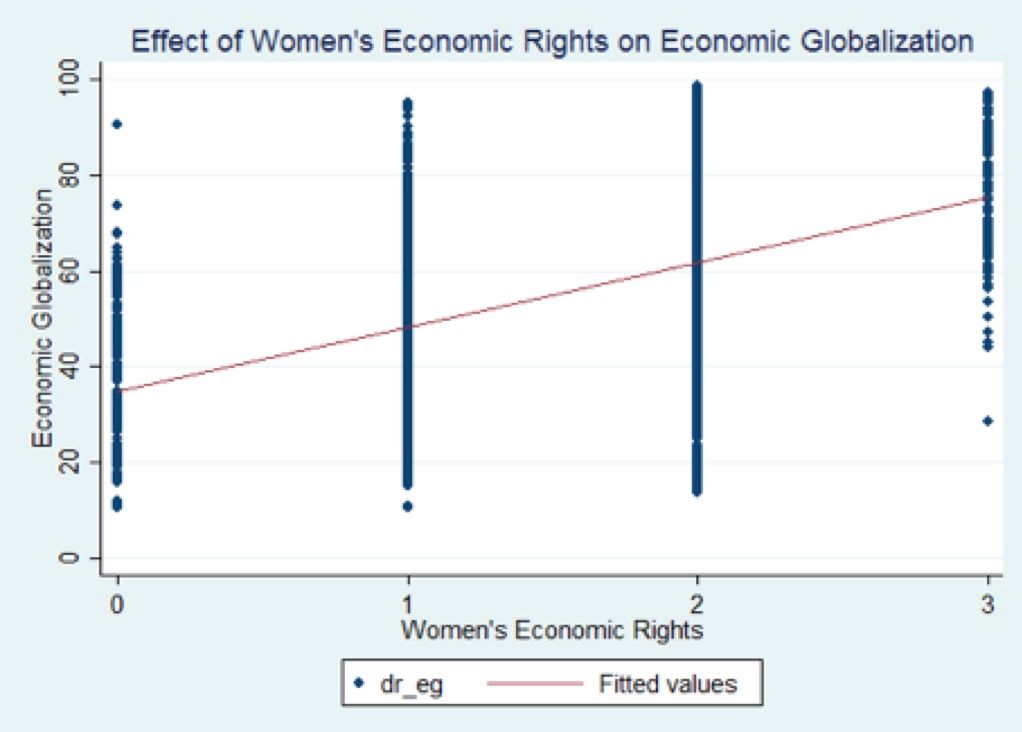

To establish a relationship between the independent and dependent variable, I created a simple plot-point graph with a line of best fit to ascertain in which direction a potential relationship might move. Graph 1 indicates that there is a potential positive relationship between women’s economic rights and economic globalization. The OLS regression tests the legitimacy of this relationship.

Graph 1. Effect of Women’s Economic Rights on Economic Globalization

As mentioned earlier, there are three primary control variables accounted for in the analysis. For the sake of statistical simplicity, I altered the polity variable from the QOG database by amending the range from 0 to 20 rather than -10 to 10. It scores 182 nations in a time series analysis from 1946-2014, with scores ranging from strongly autocratic (0) to strongly democratic (20). A second control variable for real GDP per capita measures 190 nations between 1950 and 2000.

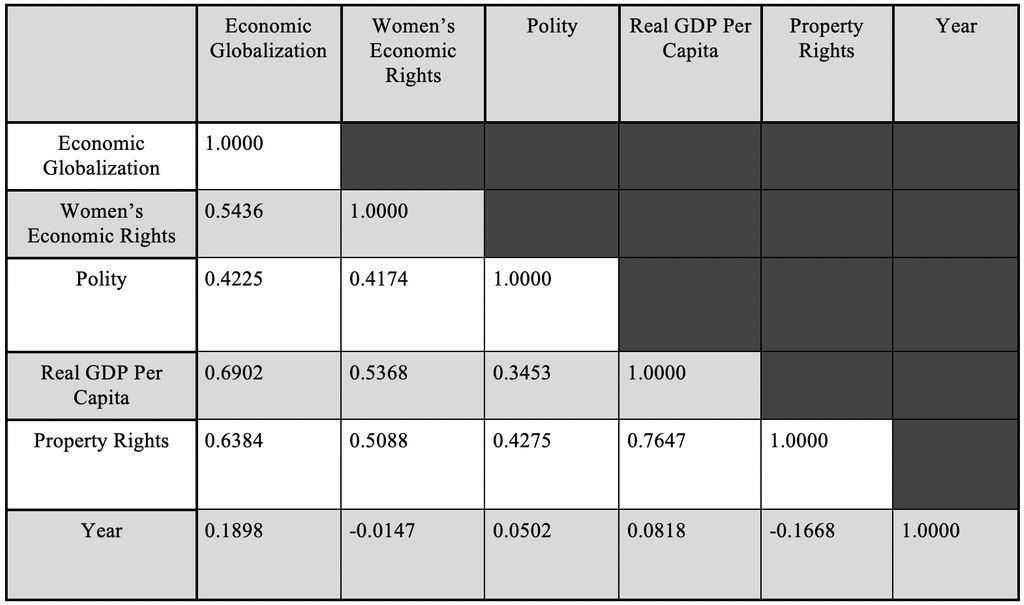

Finally, the property rights variable is borrowed from the Heritage Foundation property rights index; it is a continuous variable that ranges from 0-100 in 182 nations across the time span 1995-2017. From the QOG website, this variable measures the “degree to which a country's laws protect private property rights and the degree to which its government enforces those laws,” the “possibility that private property will be expropriated,” the “independence of the judiciary” orcorruptiontherein, and the “ability of individuals and businesses to enforce contracts.” (2018) Year is added to the model as a control variable to account for natural progress in economic globalization, and to see if any of the other control variables, or the independent variable, accelerate economic globalization. In the previous section, a brief qualitative review of potential correlation between the control and primary variables established the theoretical reasoning for selecting these controls. Table 1 displays the Pearsoncorrelation figures among all the variables, in which I found a non-trivial correlation among all the control variables, the dependent, and the independent variable. In other words, all of these variables could, indeed, be interrelated as aspects of political and economic liberalism that each independently have an effect on economic globalization.

Table 1. Pearson Correlation Among Variables

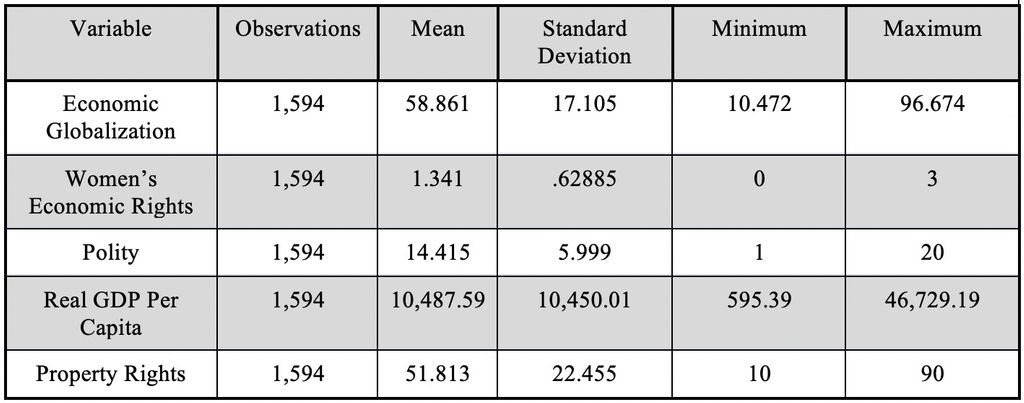

For the purposes of the analysis of my results, I include the summary statistics for each of these variables. Table 2 outlines the number of observations (N), the range of values in each variable stretching from the minimum value to the maximum value, and the mean value for each variable.

Table 2. Summary Statistics

Results and Analysis

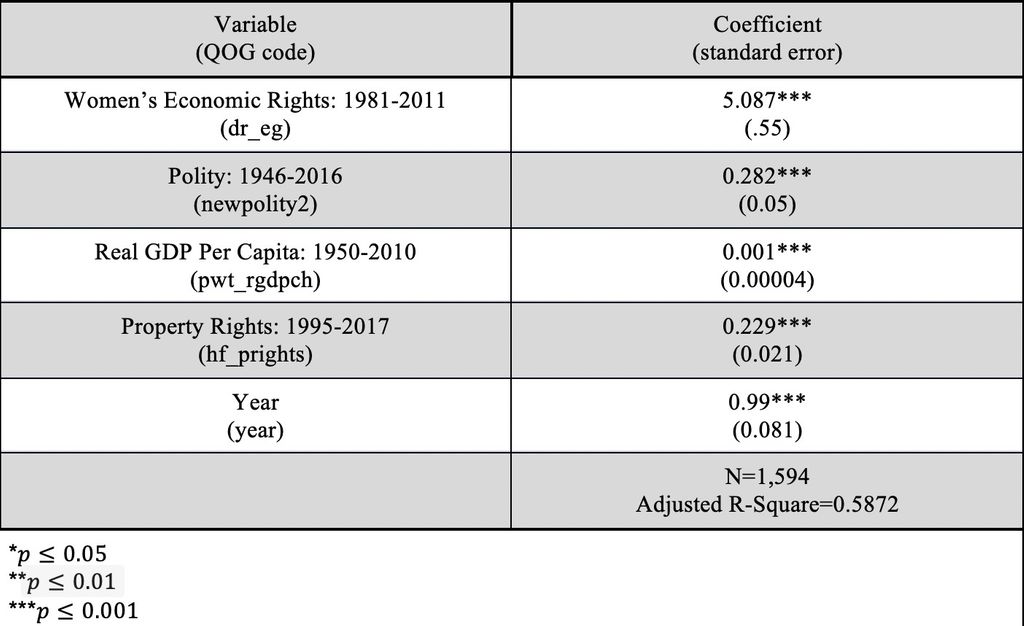

Table 3 details the results of the OLS regression analysis, expressing the levels of economic globalization between 1970-2014 according to the dependent variable, women’s economic rights, and the three control variables. Reported in the table are the variable coefficients and their standard errors. Women’s economic rights has a coefficient of 5.08, meaning that every one unit increase in the ordinal women’s economic rights variable corresponds to 5.08 increase in the economic globalization score, which ranges from 0-100. Most importantly, the p-value of this relationship was 0.000, demonstrating a statistically significant relationship between the two variables. Notably, each control variable also shared a statistically significant relationship with economic globalization, with p-values of 0.000. Finally, the R-square value indicates that almost 60% of the variation in economic globalization can be attributed to the five variables (includingyear), which represents a major portion of the variation in levels of economic globalization.

Table 3. Coefficient Estimates, Levels of Economic Globalization 1970-2014: OLS Regression Model

Overall, it appears that the initial hypothesis is considerably supported by the results of this analysis. Women’s economic rights do significantly impact economic globalization, and to an impressive extent. A one point increase in women’s economic rights, measured by degree of legal protections in countries over the time period being analyzed from the scale of 0-3, is associated with a 5% increase in economic globalization. Economic globalization is advanced in societies that protect property rights, possess higher levels of democracy, and which enjoy higher levels of GDP per capita. My research indicates that these variables are correlated as characteristics of modern, liberal states. This analysis identifies women’s economic rights as another factor of liberal nations which impacts economic globalization. Since economic development is associated with economic globalization, women’s economic rights should accelerate international economic development. It would therefore be advisable for policymakers to enable the greatest extent of women’s economic rights by legally protecting their independent right to choose work, own property, and take paid maternity leave without control by male partners or punitive retribution.

Conclusion

A very large body of literature is dedicated to the impact of political, social, and economic globalization on women’s rights and human rights. Identifying causal relationships between trade, FDI, international organizations, and other global phenomenon like the digital revolution and human rights, scholars have reached many conclusions regarding globalization’s positive effects within societies (Bayes and Tohidi 2001; Giddens and Hutton 2001; Twiss 2004; Gelleny and Richards 2007; Ouedraogo and Marlet 2018). Largely ignored, however, is a review of the effects of women’s advancement within societies on economic globalization. Can greater women’s economic rights domestically accelerate a nation’s level of economic globalization? This question initially seems counterintuitive against the backdrop of existing scholarly literature, yet classical economic theory would dictate that an increase in the extent of the market would deepen specialization through the division of labor and result in additional international trade. Neoclassical theory identified a theory of human capital that attracts investment and induces economic growth, a theory that must be applicable to women’s rights (Dutta and Osei-Yeboah 2010; Abney and Laya 2018). Therefore, I initially hypothesized that an increase in women’s economic rights would significantly increase the extent of economic globalization. Through both qualitative and quantitative review, my results indicated that an increase in women’s economic rights, measured by ordinal degrees of legal protections, does indeed have a positive and statistically significant relationship with economic globalization.

Some feminist scholars have espoused anti-capitalist sentiments due to its supposedly exploitative history and patriarchal structure (Cho 2013; Erauw 2009; Gaddis and Klasen 2014) . Yet, these societal constructs have little to do with market-oriented feminist economics, in which the principles of capitalist, democratic states can advance the cause of women’s equality once formerly discriminatory government policies are written out of existence. Scholars who substantiated the need for limiting restrictive policies include some of the same names just mentioned, such as Erauw. My theoretical foundations were based in combining this idea with scholarly research on the capability of women’s rights or human rights to attract FDI (Abney and Laya 2018; Shannon and Robert Blanton 2011; Dutta and Osei-Yeboah 2010). Existing literature aided in the pursuit of my research question, but the paper was necessary to fill a void in existing literature. No scholars had discussed the relevance of economic theory in analyzing whether women’s economic rights accelerated economic globalization by expanding the extent of the market.

Bayes and Tohidi provided an interesting idea to begin the analysis by claiming women’s rights to be a recently added characteristic of a global cohort of modern, liberal, democratic, and capitalist states. Scholars identified other characteristics of modern states that might impact globalization, including democratization (Lemke 2016; Ouedraogo and Marlet 2018), economic development (Dutta and Osei-Yeboah 2010; Abney and Laya 2018), and property rights (Lemke 2016). My OLS regression found a statistically significant relationship between all three of these variables and economic globalization, accounting for 60% of the variation in economic globalization when also including women’s economic rights. Although not included in this paper, future research could certainly break the indices down more to demonstrate independently focused relationships between each facet of economic globalization. Additionally, educational attainment was a popular topic in existing literature that I believe could be explored more in the context of FDI. Many scholars claimed that low levels of women’s economic rights but high levels of educational attainment attract foreign investment, yet these analyses were cross-sectional. It would be interesting to test whether a long term, time-series analysis found this phenomenon to decrease as women graduated with postsecondary degrees and entered the skilled labor force with greater economic equality.

Given the results of my analysis and the theoretical framework, I concluded that greater legal protections for women would have a tremendously positive impact on global development and impoverished populations around the world. Policymakers must extend these legal protections to women to advance their own global economic interests. In the words of Melinda Gates during the 2016 World Economic Forum, “We’ve all come to recognize – prime ministers, presidents, heads of companies – if we want this increase … in GDP, you have to get the other half working and participating in the economy.”