Sir Walter Scott

Aug 22, 2019 • 142 views

SIR WALTER SCOTT

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832) was a Scottish historical novelist, poet, playwright and historian.

His Life

Early Life

Sir Walter Scott was born in Edinburgh, of an ancient stock of Border freebooters. At the age of eighteen months he was crippled for life by a childish ailment; and though he grew up to be a man of great physical robustness he never lost his lameness. He was educated at the High School of Edinburgh and at the university; and there he developed that powerful memory which, though it rejected things of no interest to it, held in tenacious grasp a great store of miscellaneous knowledge. His father was a lawyer, and Scott himself was called to the Scottish Bar (1792). As a pleader he had little success, for he was much more interested in the lore and antiquities of the country. He was glad, therefore, to accept a small legal appointment as Sheriff of Selkirkshire (1799). Just before this, after an unsuccessful love-affair with a Perthshire lady, he had married the daughter of a French exile. In 1806 he obtained the valuable post of Clerk of Session, but for six years he received no salary, as the post was still held by an invalid nominally in charge.

In 1812, on receipt of his first salary as Clerk of Session, he removed from his pleasant home of Ashiestiel to Abbotsford, a small estate near Melrose. For the place he paid £4000, which he characteristicallyobtained half by borrowing and half on security of the next poem Rokeby, still unwritten. During the next dozen years he played the laird at Abbotsford, keeping open house, sinking vast sums of money in enlarging his territory, and adorning the house in a manner that was frequently in the reverse of good taste. In 1826 came the crash. In 1802 he had assisted a Border printer, James Ballantyne, to establish a business at Edinburgh. In 1805 Scott became secretly a partner. As a printing firm the concern was a fair success; but in an evil moment, in 1809, Scott, with another brother, John Ballantyne, started a publishing business. The new firm was poorly managed from the beginning; in 1814 it was only the publication of Waverley that kept it on its legs, but the enormous success of the later Waverley Novels gave it abounding prosperity-for the time. Then John Ballantyne, a reckless fellow, plunged heavily into further commitments, which entailed great loss; Scott in his easy fashion also drew heavily upon the firm's funds; and in 1826 the whole erection tumbled into ruin. With great courage and sterling honesty Scott refused to take the course that the other principals accepted naturally, and compound with his creditors. Instead he attempted what turned out to be the impossible task of paying the debt and surviving it. His liabilities amounted to £117,000, and before he died he had cleared off £70,000. After his death the remainder was made good, chiefly from the proceeds of Lockhart's Life, and his creditors were paid in full.

The gigantic efforts he made brought about his death. He had a slight paralytic seizure in 1830. It passed, but it left him with a clouded brain. He refused to desist from novel-writing, or even to slacken the pace. Other illness followed, his early lameness becoming more marked. After an ineffectual journey to Italy, he returned to Abbotsford, and died within sound of the river he loved so well.

His Work

His Poetry

Scott's earliest poetical efforts were translations from the German. Lenore (1796), the most considerable of them, is crude enough, but it has much of his later vigour and clatter. In 1802 appeared the first two volumes of The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, to be followed by a third volume in the next year. In some respects the work is a compilation of old material; but Scott patched up the ancient pieces when it was necessary, and added some original poems of his own, which were done in the ancient manner. The best of his own contributions, such as The Eve of St John, have a strong infusion of the ancient force and fire, as well as a grimly supernatural element.

In Rokeby (1813) the scene shifts to the North of England. As a whole this poem is inferior to its predecessors, but some of the lyrics have a seriousness and depth of tone that are quite uncommon in the spur-and-feather pageantry of Scott's verse. The Bridal of Triermain (1813) and The Lord of the Isles (1814) mark a decline in quality.

In addition to longer poems Scott composed many lyrics, some of which are found in the lays, others in his novels, and some of which were contributed to magazines and similar publications.Though his lyrical note is on occasion uncertain, these poems are generally of a more sustained quality than his narrative work, and, to modern tastes, Scott is here seen at his best. One eminent critic has even gone so far as to describe him as the chief lyrical poet between Burns or Blake and Shelley. Though he is no love poet, he successfully handles a wide variety of subjects, from the hearty gaiety of Waken, lords and ladies gay or Bonny Dundee to the martial ardour of Pibroch of Donuil Dhu or the moving, elegiac sadness of Proud Maisie.

His Prose

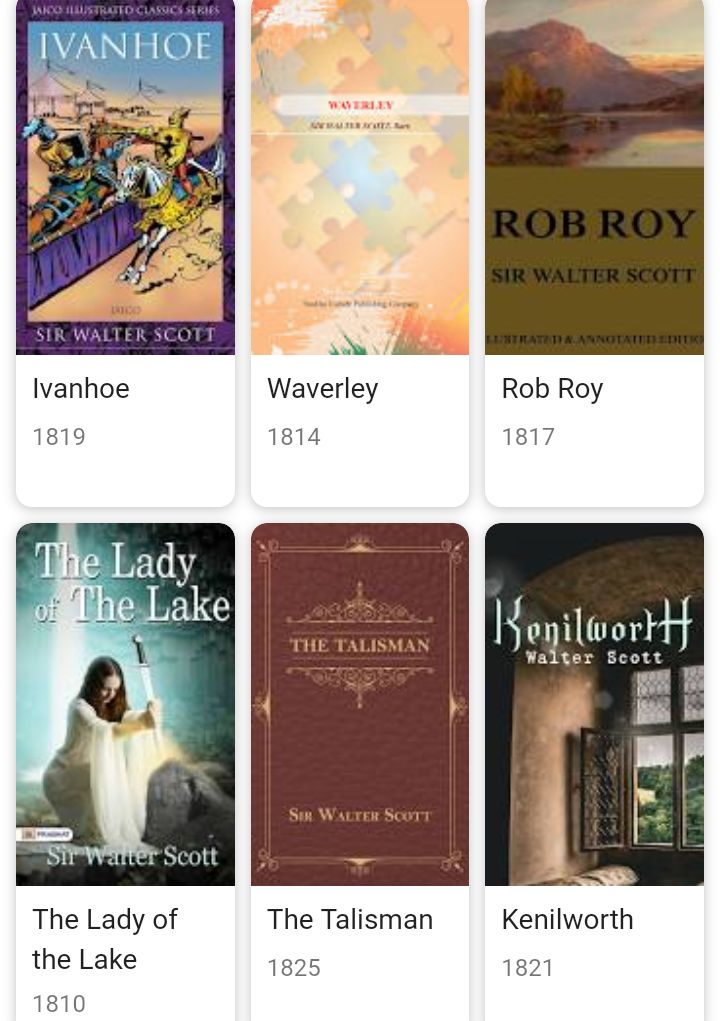

About 1814 Scott largely gave up writing poetry, and save for short pieces, mainly in the novels, wrote no more in verse. As he confessed in the last year of his life, Byron had 'bet' him by producing verse tales that were fast swallowing up by the popularity of his own. In 1814 Scott returned to a fragment of a Jacobite prose romance that he had started and left unfinished in 1805. He left the opening chapters as they stood, and on to them tacked a rapid and brilliant narrative dealing with the Forty-five. This made the novel Waverley, which was issued anonymously in 1814. Owing chiefly to its ponderous and lifeless beginning, the book hung fire for a space; but the remarkable remainder was almost bound to make it a success. After Waverley Scott went on from strength to strength: Guy Mannering (1815), The Antiquary (1816), The Black Dwarf (1816), Old Mortality (1816), Rob Roy (1818), The Heart of Midlothian (1818), The Bride of Lammermoor (1819), and A Legend of Montrose (1819). All these novels deal with scenes in Scotland, but not all with historical Scotland. They are not of equal merit, and the weakest is The Black Dwarf. Scott now turned his gaze abroad, producing Ivanhoe (1820), the scene of which is Plantagenet England; then turned again to Scotland and suffered failure with The Monastery (1820), though he triumphantly rehabilitated himself with The Abbot (1820), a sequel to the last. Henceforth he ranged abroad or stayed at home as he fancied in Kenilworth (1821), The Pirate (1822), The Fortunes of Nigel (1822), Peveril of the Peak (1823), Quentin Durward (1823), St Ronan's Well (1824), Redgauntlet (1824), The Betrothed (1825), and The Talisman (1825). By this time such enormous productivity was telling even on his gigantic powers. In the latter books the narrative is often heavier, the humour more cumbrous, and the descriptions more laboured.

Then came the financial deluge, and Scott began a losing battle against misfortune and disease. But even yet the odds were not too great for him; for in succession appeared Woodstock (1826), The Fair Maid of Perth (1828), Anne of Geierstein (1829), Count Robert of Paris (1832), and Castle Dangerous (1832). The last works were dictated from the depths of mental and bodily anguish, and the furrows of mind and brow are all over them. Yet frequently the old spirit revives and the ancient glory is renewed.

It should never be forgotten that along with these literary labours Scott was filling the office of Clerk of Session, was laboriously performing the duties of a Border laird, and was compiling a mass of miscellaneous prose. Among this last are his editions of Dryden (1808) and Swift (1814), heavy tasks in themselves, the Lives of the Novelists (1821-24): the Life of Napoleon (1827), a gigantic work that cost him more labour than ten novels; and the admirable Tales of a Grandfather (1828-30). His miscellaneous articles, pamphlets, journals, and letters are a legion in themselves.

Features of his Novels

Rapidity of Production. Scott's great success as a novelist led to some positive evils, the greatest of which was a too great haste in the composition of his stories. His haphazard financial methods, which often led to his drawing upon future profits, also tended to over production. Haste is visible in the construction of his plots, which are frequently hurriedly improvised, developed carelessly, and finished anyhow. As for his style, it is spacious and ornate, but he has little ear for rhythm and melody, and his sentences are apt to be shapeless. The same haste is seen in the handling of his characters, which sometimes finish weakly after they have begun strongly. An outstanding case of this is Mike Lambourne in Kenilworth. It is doubtful if Scott would have done any better if he had taken greater pains. He himself admitted, and to a certain extent gloried in, his slapdash methods. So he must stand the inevitable criticisms that arise when his methods are examined.

His contribution to the novel is very great indeed. To the historical novel he brought a knowledge that was not pedantically exact, but manageable, wide and bountiful. To the sum of this knowledge he added a life-giving force, a vitalizing energy, insight, and a genial dexterity that made the historical novel an entirely new species. Earlier historical novels, such as Clara Reeve's Old English Baron (1777) and Miss Porter's The Scottish Chiefs (1810), had been lifeless productions; but in the hands of Scott the historical novel became of the first importance, so much so that for a generation after his time it was done almost to death. It should also be noted that he did much to develop the domestic novel, which had several representatives in the Waverley series, such as Guy Mannering and The Antiquary. To this type of fiction he added freshness, as well as his broad and sane handling of character and incident.

His Shakespearean Qualities Scott has often been called the prose Shakespeare, and in several respects the comparison is fairly just. He resembles Shakespeare in the free manner in which he ranges high and low, right and left, in his search for material. On the other hand, in his character-drawing he lacks much of the Elizabethan's deep penetration. His villains are often melodramatic and his heroes and heroines wooden and dull. His best figures are either Lowland Scots of the middle and lower classes or eccentrics, whose idiosyncrasies are skilfully kept within bounds. He has much of Shakespeare's genial, tolerant humour, in which he strongly resembles also his great predecessor Fielding. It is probably in this large urbanity that the resemblance to Shakespeare strongly.