Beirut Of The Mind

Jun 26, 2019 • 1 view

An iconic city retrieves its romance from the wreckage of war

HAIDER AMACHA HELD on to the gun, made it his dining and sleeping companion for the 16-year-long civil war in Beirut. Thirty years later, standing in front of next generation Beirutis, he kick starts his story with the memory of a toy he carved out of clay as a child.

“Give your children toys so they never pick up a gun,” he says with teary eyes and a deep voice at a storytelling event in Beirut.

A fighter from 1975 to 1990, Haider is narrating parts of his life, which resemble those of many others involved in the conflict. Addressing a diverse audience cutting across sect, religion, ethnicities and nationalities at a popular café called Dar Bistro, Haider is giving a voice to all those who lost a part of themselves in the bloody civil war.

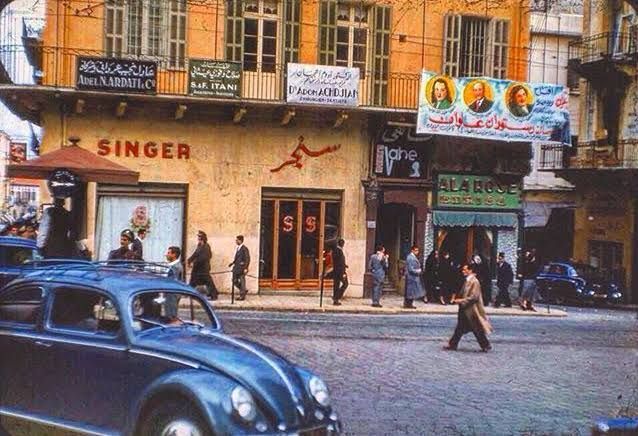

In the 60s, Beirut had the image of a playground of the region’s most affluent and of a vibrant place for Arab intellectuals. It was a holiday spot for royals and celebrities and was spoken of as the ‘Paris of the East’. Beirut boasted of hosting the likes of Brigitte Bardot andLawrence of Arabiastar Peter O’Toole. But the fame was chased by misery. The following two decades saw mayhem. At least 120,000 people were killed and over half a million displaced. By the end of it, Haider feels, it was a war without a clear enemy.

“We stopped knowing who our enemy was,” says Haider. He started off as a fighter with one quest—that Palestinians get their land back and return home. Ironically, over the course of the war, Palestinians also became an enemy.

“They stole our cows and sheep,” he tells the gathering.

Haider is not warning his listeners about Palestinians but arguing against their being used as pawns by ambitious politicians and their projects.

“Be cautious of big slogans and big causes,” he tells the sombre crowd.

Haider is sharing his nightmare in the hope of mitigating his own pain and helping others like him who are reeling under it.

Beirut still bears the marks of the colossal tragedy. The city is littered with high-rises and a residential block next to your home or hotel is quite likely punched with gaping holes. Such buildings are as much a part of the landscape as the corniche. Some in Beirut may have forgotten the years of war while others pretend to have moved on, but most hope that with time their memories will get faint and begin to heal. Worryingly, in the 27 years since the end of the armed conflict, nothing has been done to resolve the differences or reconcile the warring sides, and the torment of Beirutis of that generation carries on.

Hakaya storytelling sessions, one of which Haider spoke at, are an attempt to share stories in a neutral space. In the Middle East, Hakawatis or storytellers have been a part of the culture for centuries, with facts and fables narrated orally in market squares this way. But those at this Hakaya event received their inspiration from Moth Radio Hour, a non-profit organisation in New York which features true stories told live on stage without any script or props. Over the last few years, Beirut has seen a resurgence of the tradition in the cafes of the city led by people like Dana Ballout. She is among those who decided to revive the storytelling spirit by starting these sessions in a cosmopolitan but troubled city. “We wanted to create a non-judgemental, safe space for people to hear their stories,” Dana tells me via a voice message.

Advocating tolerance and cohesion, such evenings also bring together mixed social groups. Hakaya and Cliffhangers, which is another group organising these events, provide space for those like Haider to talk about their lives and experiences. In the absence of any programme by the state, such initiatives are the only available balm for festering wounds.

Ziad, a Muslim, and Assad, a Maronite Christian, also share their stories at the Hakaya storytelling session. Like Haider, they were fighters in the civil war and fought on opposing sides. Ziad and Assad once aimed their guns at each other, but now exchange banter.

Hakaya storytelling sessions, held in the spirit of an old Middle Eastern tradition, are an attempt to share stories in a neutral space and help people put the trauma of violence behind them

“I can’t listen to this old man and his old ideas,” Ziad mocks Assad. “Yeah, give him a candy, it is the first day he has worn trousers,” Assad fires back.

The repartee is refreshing and real, yet paradoxically it seems like a cover to hide the gashes left by the war.

Both speak of a sense of regret while at war, firing at a faceless assumed enemy. They say they remember feeling helpless and so caught up in the situation that it made it difficult to walk away.

“I felt like stopping many times, but couldn’t because you get so absorbed in it and you think you are fighting for your comrades,” Ziad says.

Common guilt and mutual apology brought Ziad and Assad together years after war.

“We had to do something and not stay quiet,” says Ziad.

Assad adds, “My son felt disgusted next to a mosque. How could I let that go on? I had to tell him what I did and why he must never repeat it.”

The realisation that they must talk about their actions dawned on them when they saw Beirut slipping into one crisis after another. From Christian-Muslim and Lebanese-Palestinian, the theatre of conflict had shifted to Shia-Sunni rivalry by the turn of the century. In 2008, Sunni militias supported by the government clashed with the Shia militia of the Hizbollah after the government declared the latter’s telecom network illegal. Hizbollah fighters took to the streets and Beirut was under siege. The sons of Ziad and Assad were by now the same age as their fathers when they first picked up a weapon. This was a wake-up call for the once-gun-totting parents, and Ziad and Assad decided to talk about what they had done to their sons and to the Lebanese youth. Both Zaid and Assad believe the problems that led to the crisis during their time have not disappeared and hence the fear of another violent confrontation in Beirut remains real.

“The warlords of the civil war became politicians, deepening the divide,” Zaid says of the political situation in Lebanon. The political system in the country is consociationalism, under which the highest offices are proportionately reserved for representatives of certain religious communities. The president is a Christian, the prime minister a Sunni and the speaker of the House a Shia. Political power is thus shared, but on the basis of religious and sectarian identity, and that, according to Ziad and Assad, magnifies problems rather than resolve them.

“My sisters and other Christians still don’t venture into Ras Beirut.” Assad speaks of the differences that live on almost three decades after the war. The social fabric of the city was rent asunder, splitting the population by their faith. Ras Beirut was once home to Christians and Muslims alike, but the Christians left during the war and have still not returned.

“The same divisions are now visible in Shia-Sunni neighbourhoods,” Ziad says.

Storytelling events are a way for both to communicate with a younger population and explain why Beirut must never repeat history. A history that the schools of Beirut refuse to teach their students. There is no structured attempt to manage trans-generational trauma.

Haunted by the events of the 80s, Zaid and Assad decided to come out with their crimes and vowed to hang themselves publicly if that’s what closure called for. The last straw for them was the riots between the Sunnis of Bab al-Tabbaneh and Alawites— an offshoot of the Shia sect—of Jabel Mohsin, two localities. Along with other fighters, both men and women, Ziad and Assad launched ‘Fighters for Justice’. Aside from attending other events, Ziad, Assad and other former fighters also share their experiences through this group.

“We the ex-fighters spoke to the new fighters of Tabbaneh and Mohsin to warn them against the chaos their quarrel would unleash,” Ziad says, as Assad nods in agreement.

I met Zaid and Assad at a coffee shop in a mall, facing the memorial of the civil war, called Beit Beirut or the House of Beirut. It stands on the green line or the stretch that separated the city in two. The building was strategically located and provided a vantage point to snipers. Serving as a reminder of the bloodbath and hopefully an example of what Beirut must never be, Beit Beirut is exhibiting pictures of some of those who lived in the building during the civil war but later vanished. Laid out were scratched, half burnt and decaying family portraits and salvaged pictures of dressed-up women. In one of the photos damaged with rust marks, a boy of about 10 or 12 years is holding on to something dearly and posing for the camera. His story was interrupted and cut short.

Haider, Zaid and Assad have found a way of sharing their tales, but thousands disappeared without a word.

Although at peace, Beirut continues to bear a certain fragility. Whole neighbourhoods are dominated by either sect or religion and exchanges between the communities are mostly commercial.

In the other part of Beirut, youth are joining the ranks of Iran’s proxy in Lebanon, the Hizbollah, which is dedicated to the cause of ‘Death to America and Israel’. Again, Beirut has become a playground, not of the Arab elite, but of regional powers like Saudi Arabia and Iran. The two Islamic powers are battling it out for dominance of the Middle East, and Lebanon has become a frontline state for this Saudi-Iranian tussle.

Beirut’s stability and future are uncertain. It is struggling to find coping methods for the lingering aftermath of the civil war, a less than effective government, a refugee crisis and the fallout of other geopolitical wars. Yet, the city displays resilience and is a shining star in an otherwise troubled region. It is a city on the edge, under threat from enemies within and outside, and that makes being here all the more interesting.