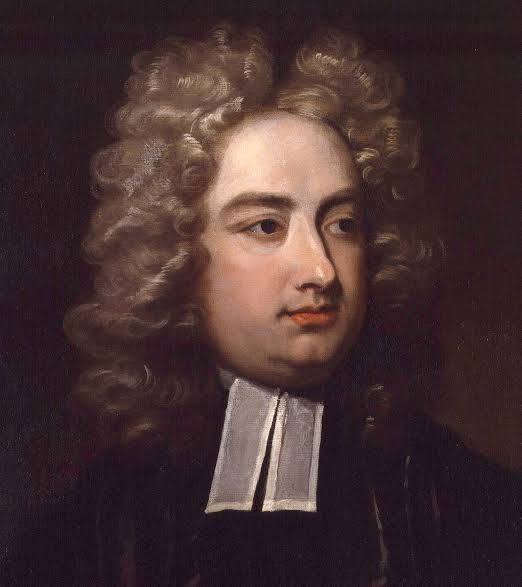

Jonathan Swift

Aug 25, 2019 • 233 views

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667–19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet and cleric who became Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin.

His Life

Swift was born in Dublin, and, though both his parents were English, his connexion with Ireland was to be maintained more or less closely till the day he died. His father dying before Jonathan's birth, the boy was thrown upon the charity of an uncle, who paid for his education in Ireland. He seems to have been very wretched both at his school at Kilkenny and at Trinity College, Dublin, where his experiences went to confirm in him that savage Melancholia that was to endure all his life. Much of this distemper was due to purely physical causes, for he suffered from an affection of the ear that ultimately touched his brain and caused insanity. In 1686, at the age of nineteen, he left Trinity College (it is said in disgrace), and in 1689 entered the household of his famous kinsman Sir William Temple, under whose encouragement he took holy orders, and on the death of Temple in 1699 obtained other secretarial and ecclesiastical appointments. His real chance came in 1710, when the Tories overthrew the Marlborough faction and came into office. To them Swift devoted the gigantic powers of his pen, became a political star of some magnitude, and, after the manner of the time, hoped for substantial rewards. He might have become a bishop, but it is said that Queen Anne objected to A Tale of a Tub and had doubts about his orthodoxy and in the wreck of the Tory party in 1715 all he could save was the Deanery of St Patrick's, in Dublin, which he had received in 1713. An embittered man, he spent the last thirty years of his life in gloom, and largely in retirement. His last years were passed in silence and, at the very end, lunacy.

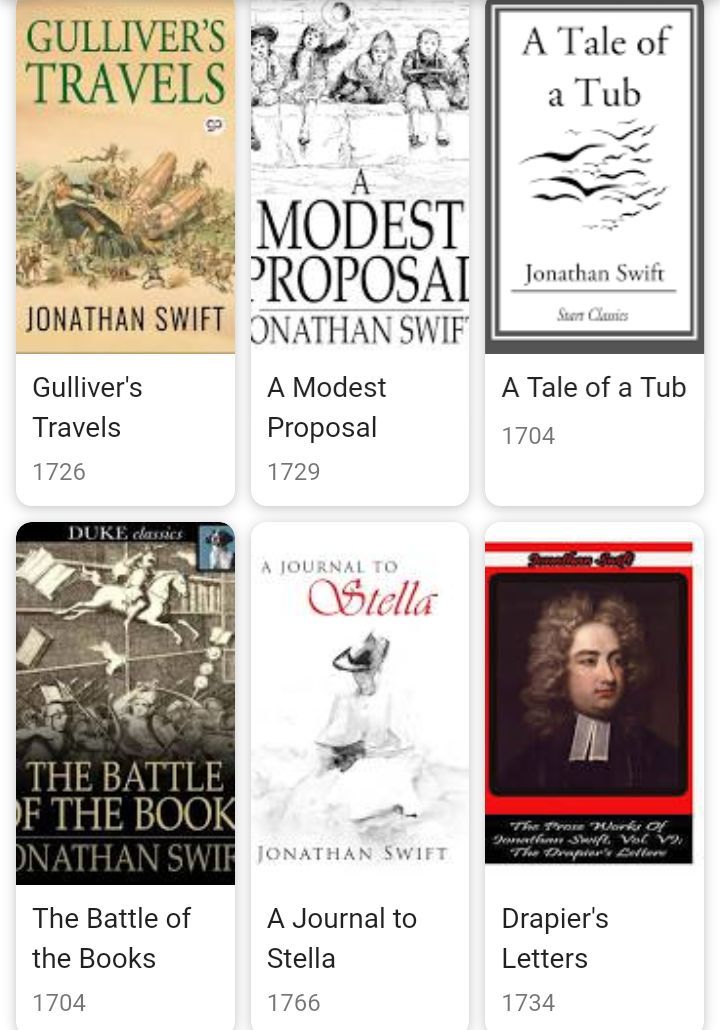

His Works

His Poetry

Swift would have been among the first to smile at any claim being advanced for him on the score of his being a great poet, though he always longed to excel in poetry, yet in bulk his verse is considerable. His poems were to a large extent recreations : odd verses (sometimes humorously doggerel) to his friends, squibs and lampoons on his political and private enemies, including the famous one on Partridge, the quack astrologer; and one longish one, Cadenus and Vanessa (1712-13), which deals with his affection for Esther Vanhomrigh. In his poems he is as a rule lighter of touch and more placable in humour than he is in his prose. His favorite metre is the octosyllabic couplet, which he handles with a dexterity that reminds the reader of Butler in Hud bras. He has lapses of taste, when he becomes coarse and vindictive; and sometimes the verse, through mere indifference, is badly strung and colloquial expressed.

The following is from some bitter verses he wrote (1731) on his own death just before the final night of madness descended. Note the fierce misery inadequately screened with savage scorn.

Yet thus, methinks, I hear 'em speak:

“See, how the Dean begins to break!

Poor gentleman, he droops apace!

You plainly find it in his face.

That old vertigo in his head

Will never leave him, till he's dead.

Besides, his memory decays:

He recollects not what he says;

He cannot call his friends to mind;

Forgets the place where last he dined;

Plies you with stories o'er and o'er;

He told them fifty times before.

How does he fancy we can sit

To hear his out-of-fashion'd wit?

But he takes up with younger folks

Who for his wine will bear his jokes.

Faith, he must make his stories shorter

Or change his comrades once a quarter:

In half the time he talks them round,

There must another set be found."

His Prose

Almost in one bound Swift attained to a mastery of English prose, and then maintained an astonishing level of excellence. His first noteworthy book was The Battle of the Books, published in 1704. The theme of this work is a well-worn one, being the dispute between ancient and modern authors. At the time Swift wrote it his patron, Sir William Temple, was engaged in the controversy on behalf of the ancients, and Swift's tract was in support of his kinsman's views. Swift gives the theme a half allegorical, mock-heroic setting, in which the books in a library at length literally contend with one another. The handling is vigorous and illuminating, and refreshed with many happy remarks and allusions. The famous passage where a bee, accidentally blundering into a spider's web, argues down the bitter remarks of the spider, is one of Swift's happiest efforts.

Swift is the greatest English satirist. Unlike Pope he restricts himself to general rather than personal attacks, and his work has a cosmic, elemental force, which is irresistible and, at times, almost frightening. His dissection of humanity shows a powerful mind relentlessly and fearlessly probing into follies and hypocrisy, but he is never merely destructive. Always underlying his work is the desire for the greater use of common sense and reason in the ordering of human affairs. Often the satire is cruel and violent, and sometimes it is coarse and repulsive-perhaps the result of his own physical disabilities, and his keen disappointment at his failure to gain the preferment which he felt himself to have merited. But the terrible savagery of A Voyage to the Houyhnhnms, and A Modest Proposal for preventing the children of poor people from being a burden to their parents (by selling them as food for the rich) should not blind us to the great range of his work. Between these two and the playfulness of Predictions for the ensuing year, 1708, by Issac Bickerstaff, Esq., or the almost boyish humour of his Discourse to prove the Antiquity of the English Tongue, there is a range of satirical force which indicates a fertility of imagination and an ingenuity of fancy unparalleled among his rivals in this field.