The Goldwater Rule

May 29, 2019 • 156 views

The Goldwater rule is the informal name for section 7 of the American Psychiatric Association's (APA) Principles of Medical Ethics, which states that it is unethical for psychiatrists to give professional opinion about public figures whom they have not examined in person, and from whom they have not obtained consent to discuss their mental health in public statements. The rule is named such after the former US Senator and 1964 US presidential candidate Barry Goldwater.

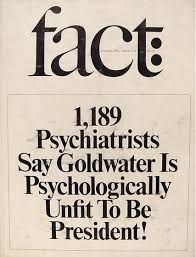

In the United States presidential election of 1964, Barry Goldwater competed with Lyndon Johnson. A survey conducted during that time by the editors of Fact magazine led to the creation of APA's ‘Goldwater Rule’ in 1973. The editors of the magazine asked 12,356 psychiatrists, “Do you believe Barry Goldwater is psychologically fit to serve as President of the United States?” and published the article titled ‘The Unconscious of a Conservative: A Special Issue on the Mind of Barry Goldwater’ where they presented 1,189 psychiatrists’ suggestions for Goldwater’s psychological unfitness to be president. Barry Goldwater sued Ralph Ginzburg, the editor of Fact Magazine, for defamation and won $75,000 in damages.

Section 7, which appeared in the first edition of the American Psychiatric Association's (APA) Principles of Medical Ethics in 1973 and is still in effect, states that:

On occasion psychiatrists are asked for an opinion about an individual who is in the light of public attention or who has disclosed information about himself/herself through public media. In such circumstances, a psychiatrist may share with the public his or her expertise about psychiatric issues in general. However, it is unethical for a psychiatrist to offer a professional opinion unless he or she has conducted an examination and has been granted proper authorization for such a statement.

The APA Ethics Code of the American Psychological Association also supports a similar rule. In 2016, American Psychological Association President Susan H. McDaniel stated the following in a letter to the New York Times in response to their article titled ‘Should Therapists Analyze Presidential Candidates?’:

Similar to the psychiatrists' Goldwater Rule, our code of ethics exhorts psychologists to ‘take precautions’ that any statements they make to the media ‘are based on their professional knowledge, training or experience in accord with appropriate psychological literature and practice’ and ‘do not indicate that a professional relationship has been established’ with people in the public eye, including political candidates...Our ethical code states that psychologists should not offer a diagnosis in the media of a living public figure they have not examined.

The American Psychoanalytic Association (APsaA), however, partly permits psychoanalysts to offer insights to help the public understand a wide range of political, artistic, cultural, historical and economic phenomena but psychoanalysts have been requested to maintain “extreme caution” when making statements to the media about public figures. The limitations of psychoanalytic inferences about individuals who have not been interviewed in depth has been duly noted by them.

In recent years, the Goldwater rule gained new attention during the campaign and election of US President Donald Trump. A number of mental health professionals were criticised for violating the Goldwater rule, as they claimed that Trump exhibited"an assortment of personality problems, including grandiosity, a lack of empathy, and 'malignant narcissism'", and that he has a "dangerous mental illness", without ever examining him in person.

John Gartner, a psychologist, and the leader of the group Duty to Warn, stated in April, 2017 that:

We have an ethical responsibility to warn the public about Donald Trump's dangerous mental illness.

Recent analysis indicates that the principle behind the Goldwater rule is not scientifically well-backed and is irrelevant in today’s society. In-person examination is not necessary in the presence of other valid sources of information. Extensive public records in the form of interviews with the media, social media accounts, interviews with friends, family and individuals familiar with the person can reveal fixed behavioural patterns. Plus, direct interviews with the concerned person may at times present factors that contribute to bias.

At present, a substantial number of mental health professionals believe it is necessary to revise and update the Goldwater rule in light of current research findings.